What i love about them, is something that happens so slowly be given a new lease of life and nature becomes even more beautiful and inspiring and the interesting 'shapes', 'lines' 'colours' created by something as simple as mist or migrating birds etc.

I'm really unsure as to how I can research this any other way than just watching videos and posting, and I feel this category is unnecessary to get peoples opinions on this topic... although i may try.

SO why do I think they are "good" - people very often just by pass the world around them and miss so much of the beauty around them, the people who have taken the time to film such events just give us a massive insight into what we are missing, there's something quite relaxing about them as well. I think it really brings the expression 'watch the world go by' "to life" and I like the thought of just being able tos sit and take it all in.

It may get a bit repetitive some of the films, but I wanted to put a selection up.

"Time-lapse photography is a cinematography technique whereby each film frame is captured at a rate much slower than it will be played back. When replayed at normal speed, time appears to be moving faster and thus lapsing. Time-lapse photography can be considered to be the opposite of high speed photography.

Processes that would normally appear subtle to the human eye, such as the motion of the sun and stars in the sky, become very pronounced. Time-lapse is the extreme version of the cinematography technique of undercranking, and can be confused with stop motion animation".

Some classic subjects of timelapse photography include:

* cloudscapes and celestial motion

* plants growing and flowers opening

* fruit rotting

* evolution of a construction project

* people in the city

The first use of time-lapse photography in a feature film was in Georges Méliès' motion picture Carrefour De L'Opera (1897). Time-lapse photography of biologic phenomena was pioneered by Jean Comandon[1] in collaboration with Pathé Frères from 1909, by F. Percy Smith in 1910 and Roman Vishniac from 1915 to 1918. Time-lapse photography was further pioneered in a series of feature films called Bergfilms (Mountain films) by Arnold Fanck, in the 1920s, including The Holy Mountain (1926).

From 1929 to 1931, R. R. Rife astonished journalists with early demonstrations of high magnification time-lapse cine-micrography[2][3] but no filmmaker can be credited for popularizing time-lapse more than Dr. John Ott, whose life-work is documented in the DVD-film "Exploring the Spectrum".

HOW DOES IT WORK

Film is often projected at 24 frame/s, meaning that 24 images appear on the screen every second. Under normal circumstances a film camera will record images at 24 frame/s. Since the projection speed and the recording speed are the same, the images onscreen appear to move normally.

Even if the film camera is set to record at a slower speed, it will still be projected at 24 frame/s. Thus the image on screen will appear to move faster.

Even if the film camera is set to record at a slower speed, it will still be projected at 24 frame/s. Thus the image on screen will appear to move faster. The change in speed of the onscreen image can be calculated by dividing the projection speed by the camera speed.

So a film that is recorded at 12 frames per second will appear to move twice as fast. Shooting at camera speeds between 8 and 22 frames usually falls into the undercranked fast motion category, with images shot at slower speeds more closely falling into the realm of time-lapse, although these distinctions of terminology have not been entirely established in all movie production circles.

Short Exposure vs. Long Exposure Time-lapse

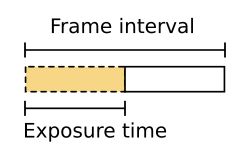

As first mentioned above, in addition to modifying the speed of the camera, it is also important to consider the relationship between the frame interval and the exposure time. This relationship essentially controls the amount of motion blur present in each frame and it is, in principle, exactly the same as adjusting the shutter angle on a movie camera. This is also known as "Dragging the shutter."

A film camera normally records film at twenty four frames per second. During each 24th of a second the film is actually exposed to light for roughly half the time. The rest of the time it is hidden behind the shutter. Thus exposure time for motion picture film is normally calculated to be one 48th of a second (1/48 second, often rounded to 1/50 second). Adjusting the shutter angle on a film camera (if its design allows) can add or reduce the amount of motion blur by changing the amount of time that the film frame is actually exposed to light.

In time-lapse photography the camera records images at a specific slow interval such as one frame every thirty seconds (1/30 frame/s). The shutter will be open for some portion of that time. In short exposure time-lapse the film is exposed to light for a normal exposure time over an abnormal frame interval. So for example the camera will be set up to expose a frame for 1/50th of a second every 30 seconds. Such a setup will create the effect of an extremely tight shutter angle giving the resulting film a stop-animation or clay-mation quality.

In long exposure time-lapse the exposure time will approximate the effects of a normal shutter angle. Normally this means that the exposure time should be half of the frame interval. Thus a 30 second frame interval should be accompanied by a 15 second exposure time to simulate a normal shutter. The resulting film will appear smooth.

The exposure time can be calculated based on the desired shutter angle effect and the frame interval with the equation:

Long exposure time-lapse is less common because it is often difficult to properly expose film at such a long period, especially in daylight situations. A film frame that is exposed for 15 seconds will receive 750 times more light than its 1/50th of a second counterpart. (Thus it will be more than 9 stops over normal exposure.) A scientific grade neutral density filter can be used to alleviate this problem.

Time-lapse camera movement

As also earlier mentioned, some of the most stunning time-lapse images are created by moving the camera during the shot. A time-lapse camera can be mounted to a moving car for example to create a notion of extreme speed.

However to achieve the effect of a simple tracking shot it is necessary to use motion control to move the camera. A motion control rig can be set to dolly or pan the camera at a glacially slow pace. When the image is projected it could appear that the camera is moving at a normal speed while the world around it is in time lapse. This juxtaposition can greatly heighten the time-lapse illusion.

The speed that the camera must move to create a perceived normal camera motion can be calculated by inverting the time-lapse equation:

Baraka was one of the first films to use this effect to its extreme. Director and cinematographer Ron Fricke designed his own motion control rigs that utilized stepper motors to pan, tilt and dolly the camera.

A panning timelapse can also be easily and inexpensively achieved by using a widely available telescope Equatorial mount with a Right ascension motor (*360 degree example using this method). Two axis pans can be achieved as well with contemporary motorized telescope mounts (*link)

A variation of these are rigs that move the camera DURING exposures of each frame of film, blurring the entire image. Under controlled conditions, usually with computers carefully making the movements during and between each frame, some exciting blurred artistic and visual effects can be achieved, especially when the camera is also mounted onto a tracking system of its own that allows for its own movement through space. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time-lapse) (lifted - purely for research purposes - no other website gave as much technological in depth analysis)

I find this one particularly interesting as it combines nature and technology together and how nature virtually destroys the scanner...

ANTS in my scanner > a five years time-lapse! from françois vautier on Vimeo.

August Stars - Time Lapse Test from Brian Harbauer on Vimeo.

Time Lapse clips from Scott Rucci on Vimeo.

Nature Timelapse from Lars H. Sørebø on Vimeo.

Stephen Wilkes - Time-Lapse: A Day at A Walmart Store from BERNSTEIN & ANDRIULLI on Vimeo.

From a business point of view this is good as it shows when the quiet part of the day is and the busiest - thus keeping staff on at the right times etc.Time Lapse of Winter Scene from mockmoon on Vimeo.

time lapse robin's nest from animal detectors on Vimeo.

A Growing Bean (Time Lapse) from Will Corban on Vimeo.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of cell division. from Daniel Mietchen on Vimeo.

The colours on this video are amazing and now I want to look at some more cell division...

Elisabeth Bridge from Time-Lapse HD on Vimeo.

Yeah, I know I said nature... but humans count...

Time Square Time Lapse from Lulis Leal on Vimeo.

Times square time lapses have always interested me... but I am unsure as to why - think it must have to do with my obsession over NYC.

Times Square Time Lapse from Jessica Pinney on Vimeo.

New York City Time Lapse from Blueglaze LLC on Vimeo.

Sydney Traffic Time Lapse from Winston Yang on Vimeo.

Through looking at videos and a comment made in the how to bit at the beginning, I do have to agree that the more interesting videos are the ones that have some camera movement - they have a more man made look and have a raw feel to them - a more creative appeal.

No comments:

Post a Comment